Rob | Posted on | 1 Comment |

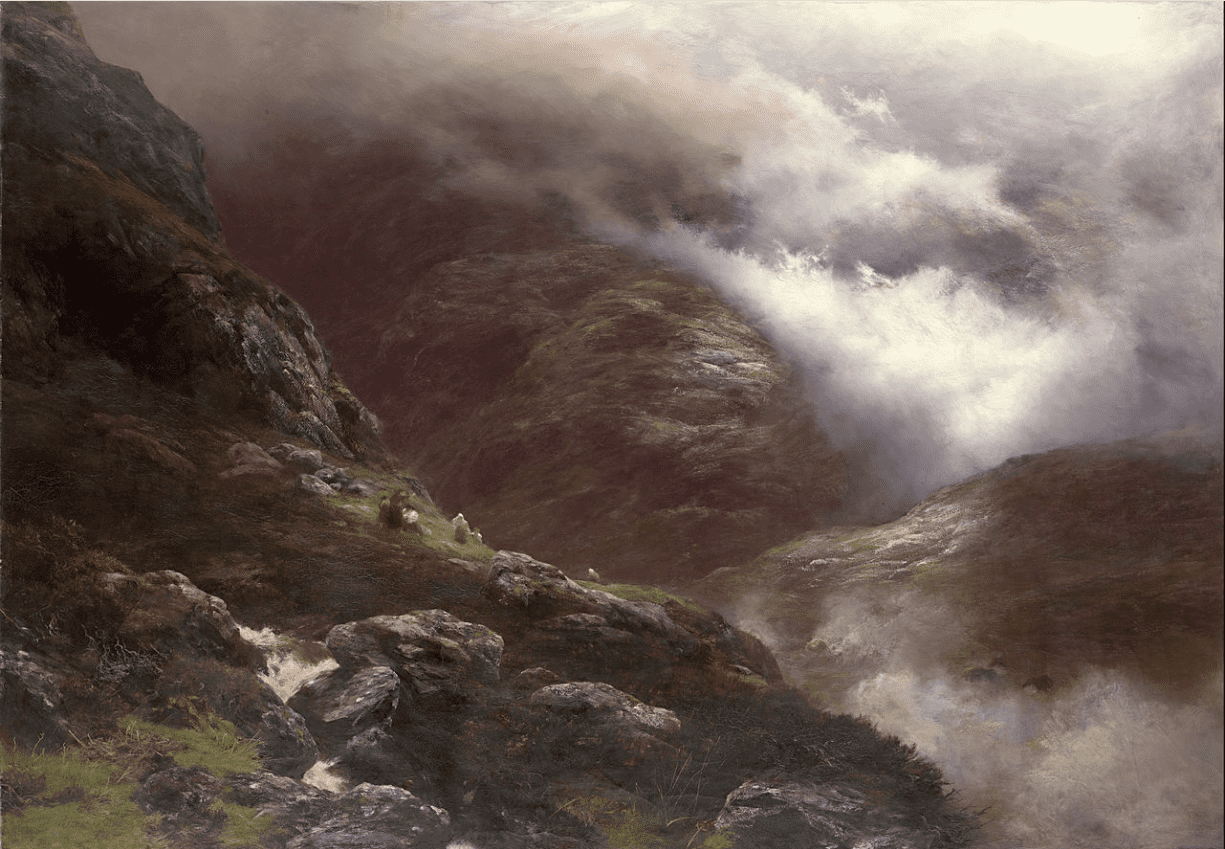

The Glencoe Massacre

Introduction

On the morning of February 13th, 1692, a garrison of crown troops led by Robert Campbell of Glenlyon awoke in the Glencoe valley in the Scottish Highlands. The Campbell soldiers, who had been staying with the MacDonalds of Glencoe clan for two weeks, began going from house to house, slaughtering the members of the clan while they slept. This brutal massacre was the result of an order from King William, delivered the evening before, that instructed the Campbell soldiers to punish the MacDonalds for their failure to sign an oath of allegiance to the King. The order was intended to set an example for other clans who might be considering rebellion against the Crown.

According to some reports, the Campbell soldiers feigned friendship and hospitality towards the MacDonalds before carrying out the attack, adding a sense of betrayal to the tragedy. The aftermath of the Glencoe Massacre was long-lasting, with the surviving MacDonalds forced to flee their homes and the Campbell soldiers facing legal and political repercussions for their actions. This dark episode in Scottish history highlights the complex feudal relations between England and Scotland, which continue to have repercussions to this day.

William of Orange's Invasion

This event starts with the crowning of King James II of England and VII of Scotland in February 1685. At the time, he was widely supported by both countries. However, his Catholicism caused concern among his predominantly Protestant subjects, and his lack of a male heir led to uncertainty about the succession. His daughter, Mary, who was Protestant, was seen as the most likely successor. This was important because previous wars had been fought over religious differences, most notably the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which had taken place just 50 years earlier.

Despite these concerns, James’s rule was accepted as a means of maintaining peace in the realm until two events in June 1685 created what was considered a political crisis. Firstly, James produced his first male heir, James Francis Edward, which could establish a Catholic dynasty and displace Mary as the next in line to the throne. Secondly, anti-Catholic riots started to increase, caused by the introduction of Sedition laws which protected the Catholic Church. The government then decided that James’s continued presence was a greater threat to stability than his removal, and they invited Dutchman William of Orange to invade and “protect the Protestant religion”.

On November 6th, 1688, William of Orange arrived in England with 14,000 men and advanced to London. Most of the 30,000-strong Royal army defected to his side, and King James went into exile on December 23rd. In April 1689, William and Mary were crowned joint monarchs of England and Ireland, and in June of that year, they were also crowned monarchs of Scotland. This was known as the Glorious Revolution, and it was seen as a bloodless takeover, despite two significant battles considered losses to King James supporters (known as Jacobites) that produced many casualties, the main battle being the Battle of Killiecrankie.

In Scotland, the Glorious Revolution had a significant impact on the relationship between the Scottish clans and the monarchy. The Highland clans had a tradition of loyalty to their chieftains rather than to the central government, and they were known for their resistance to attempts by the monarchy to exert control over them. As a result, many of the clans remained loyal to King James and refused to acknowledge William and Mary as the legitimate monarchs.

William III and his government responded by passing a series of laws aimed at bringing the Highland clans under control, including the Disarming Act of 1716 and the Dress Act of 1746. These laws effectively prohibited the wearing of traditional Highland dress and the possession of weapons, and they were enforced through military action against those who refused to comply. The harsh treatment of the Highland clans by the government may have contributed to the circumstances that led to the Glencoe Massacre, as the MacDonalds of Glencoe were seen as a symbol of resistance to government authority.

The Allegiance of the Clans and the Royal Proclamation

After William’s coronation, the issue of clan loyalty to the new monarch arose, with different interpretations and opinions on certain events and actions taken by the parties involved. In an attempt to quell any potential rebellions, William sought to secure the allegiance of the clans. Clan Campbell was one of the first to pledge their allegiance to the new King and Queen. William then used the Clan Campbell chief to discuss terms with other clans.

In June 1691, a meeting was arranged with many clan chiefs, including Alistair MacDonald of Glencoe, also known as Alistair Maclain. The Crown’s terms, delivered by John Campbell, Earl of Breadalbane, were that £12,000 would be paid as reparations to be distributed among the clans if they pledged their allegiance. Campbell, who had issues with Maclain, stated that the Glencoe clan would not receive their share due to cattle the clan had stolen from the Campbells. This outraged Maclain, and the incident became a subject of debate and interpretation.

Campbell also claimed, without authority from the king, that if the exiled King James returned to Scotland, the clans could safely break their oaths to King William to support James. This was a tactic from Campbell to get the clans to sign without restraint, but it was not the intention of the king, and it caused further debates and discussions among the clans.

Despite these issues, the clans signed the agreement, with John Campbell signing on behalf of the Crown. However, the clans were not able to decide on the distribution of the £12,000, leading King William to issue a Royal Proclamation on 26th August 1691. The proclamation stated that all clans had until 1st January 1692 to pledge their allegiance or face severe consequences. This did not sit well with John Campbell and some major clans, including the chief of MacDonalds of Glengarry, who viewed this as making their previous oath of allegiance null and void.

In early October 1691, the chiefs asked King James for permission to take the oath under the proclamation unless he could mount an invasion before the deadline, a condition all knew was impossible. It was not until 12th December that James granted his approval to the clans to pledge their allegiance for their own safety. However, the Crown was aware of this and caused further delays by arresting the messengers from France when they arrived on shore and holding them for three days. The Clan Chief of MacDonald of Glengarry finally received the document on 23rd December, but he delayed sharing the information with the other clans until 28th December, leading to further debates and differing interpretations among the clans.

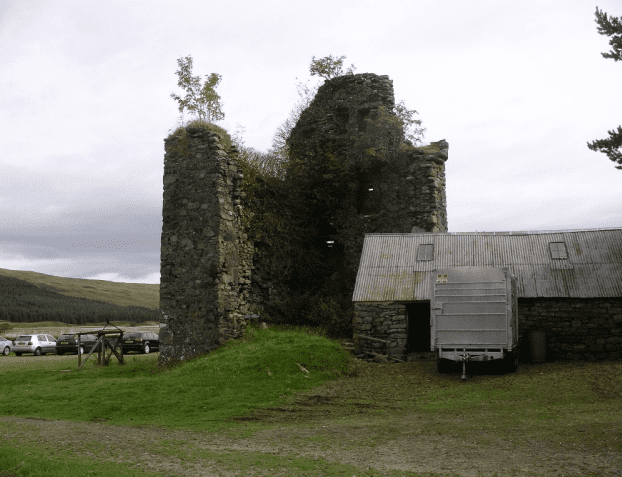

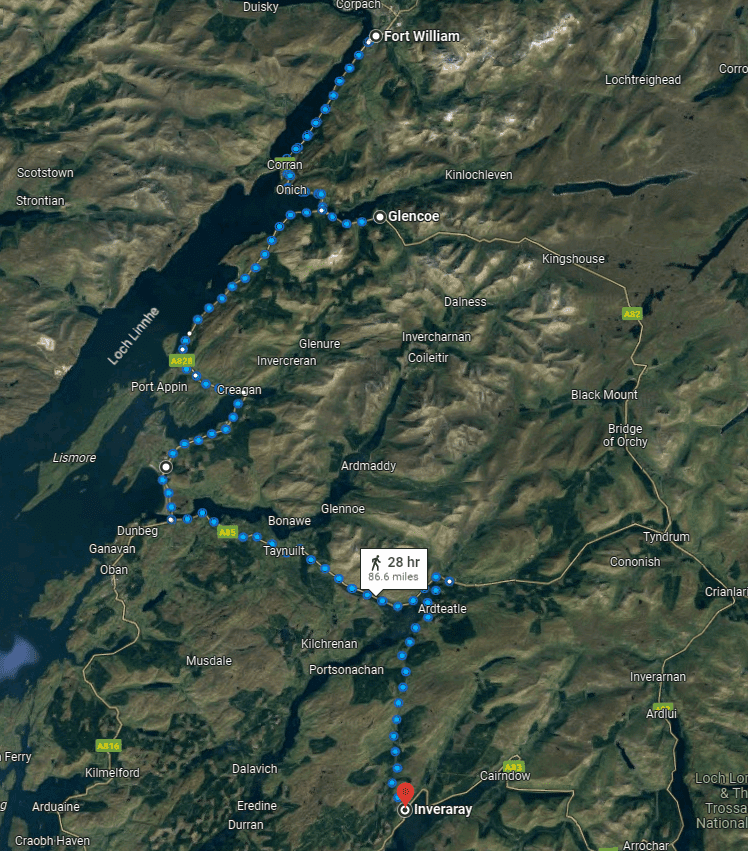

Maclain's Delayed Oath and the Letter of Protection

On December 30th, Alistair Maclain of Glencoe set out for Fort William to pledge his allegiance to King William. He intended to give his oath to his friend, Lieutenant Colonel John Hill, but upon arriving at Fort William, he learned that Hill was not available in his office until January 1st. When they finally met on January 1st, Hill told Maclain that he could not perform the task and instead directed him to deliver his oath to Sir Colin Campbell, the local magistrate in Inverary, located 60 miles away. Hill gave Maclain a letter of protection, guaranteeing his safety, and stating that Maclain had done everything in his power to take the oath before the deadline.

Maclain made his pledge on January 6th, 1692 and returned home under the impression that he had fulfilled his obligation without consequence. However, as we will see, the events that followed would have dire consequences for Maclain and his clan.

Prelude to Tragedy

After many clans made late pledges, King William and John Campbell decided to make an example of those who had not yet pledged loyalty. Despite receiving a letter of protection, the MacDonalds of Glencoe were considered a small and unprotected clan. Other clans that were late to pledge had soldiers and fortifications to handle any conflict, but Glencoe did not. King William then ordered the genocide of the MacDonalds of Glencoe, and the order was passed through several officials, including Secretary of State John Dalrymple and Thomas Livingston, who was in charge of the Scottish army. The order eventually made its way to John Hill, who procrastinated passing it on. He eventually gave it to Colonel James Hamilton and Major Robert Duncanson, who were given the support of 800 troops to carry out the order. Meanwhile, in late January, Royal soldiers arrived in Glencoe and were welcomed by Alistair Maclain, Chief of the MacDonalds of Glencoe, who invited them to stay with various families in the clan, including Robert Campbell of Glenlyon who stayed with Maclain and his household.

The Glencoe Massacre

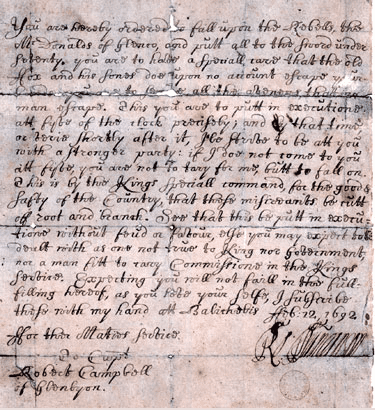

On the evening of February 12th, Robert Campbell of Glenlyon was ordered to carry out a massacre of the MacDonalds of Glencoe, with the warning that failure to do so would result in severe consequences. The orders were delivered by Argyll officer Captain Thomas Drummond, who had no respect for the MacDonalds. Drummond stayed with Campbell, likely to ensure that he carried out the orders.

The timing of the massacre was crucial because the Glen had only two entry and exit points that were surrounded by mountains. Campbell and his men would begin executing clan members at 5am and were joined by Major Duncanson with 400 men. Together, they would sweep up the Glen, killing MacDonalds and burning huts as they went. Colonel James Hamilton was to be stationed at the top of the Glen to prevent any MacDonalds from escaping.

Campbell carried out the first execution by waking Maclain and pretending the regiment was preparing to leave. After sharing a whisky, Campbell shot him. Campbell’s men then killed the members of the houses they were staying in, in a similar fashion. Gunfire alerted the MacDonalds, who tried to escape. Duncanson was two hours late and only arrived at 7am. Campbell’s men burned the houses and drove the fleeing clan members up the Glen since they were without Duncanson’s help. Hamilton’s men were also late, not arriving at the top of the Glen until 11am.

It is believed that under John Hill, a friend of Maclain, the slaughter could not be stopped. Despite protests from both Duncanson and Hamilton, who were purposely late as they believed the orders were inappropriate, many people still perished. Campbell’s men had killed about 30 MacDonalds, and it is believed that many others died from the cold and falling through the ice on the Glen during the sub-zero temperatures and storm.

Maclain’s two sons and others were able to escape at the top of the Glen, where Hamilton’s men were supposed to be stationed, thus the King’s order of genocide was not complete, and the bloodline of the Clan continues to this day. Although the crown issued further orders for the deaths of the remaining MacDonalds of Glencoe, these orders were largely ignored.

The Aftermath

The Glencoe Massacre of 1692 was a tragic event in Scottish history that had long-lasting implications. Despite the Crown’s efforts to conceal it, the papers containing Robert Campbell of Glenlyon’s orders were left in a coffee shop, leading to their discovery and subsequent publication in French newspapers. News of the massacre then spread back to England and Scotland, resulting in two inquiries.

The first inquiry, which placed blame on the Crown, was silenced by King William himself, while the second inquiry, which blamed Robert Campbell, was brought before parliament. The “murder under trust” act was applied, suggesting that Campbell and his men committed treason because they were welcomed by the MacDonalds and had formed a customary bond with them.

Although Campbell could have refused the Crown’s orders, he would have faced execution by Captain Drummond had he done so. No further consequences were imposed in response to the massacre.

The Glencoe Massacre’s impact can be seen in popular culture, such as the Red Wedding in the Song of Ice and Fire series and the Game of Thrones TV show. The legacy of the massacre lives on, as evidenced by the sign at the Clachaig Inn in Glencoe that reads “No hawkers and no Campbells,” a clear indication of the continued animosity between the MacDonalds and the Campbells.

While the MacDonalds of Glencoe were not favored by many clans, the event fueled distrust of the recent change in the monarchy, setting the stage for the next two Jacobite uprisings, including the Battle of Culloden. The aftermath of this battle is considered the greatest loss to Scottish Highland culture, leading to the end of the Clan system and the prohibition of wearing tartan and playing bagpipes.

One Comment

Well written clear explanation of a very significant event that should never have happened.